Opening of School Chapel Speech - September 9, 2019

[sing]

“The trouble with you, is the trouble with me. We’ve got two good eyes, but we still don’t see.”

[ask the students to sing]

That’s right, “The trouble with you is the trouble with me, we’ve got two good eyes, but we still don’t see.”

This is absolutely true. As I see it. Through my lens, in the way I’ve framed it. Yes, it’s true, I can see it clearly. And that is trouble, don’t you think? The trouble between us? I see it as I see it, I’m confident. But you? Who knows? There are more than 600 of us in the room right now, so double that number of eyes gazing this way or that. Looking at me. Looking at the windows, maybe looking at the people around you, or the back of the head in front of you. Seems to me it’s even bigger trouble if we say we’ve got 1200 eyes, but can barely see. But yet this seems to be the case. We’re all here, sharing in what might be described as the same experience. Yet, we’re not all seeing it the same way. This is not trouble today. But it could one day be trouble. As I see it.

We all spent part of our summer reading Into the Raging Sea, the recounting of the disaster of the El Faro. There are many ways to read the book. You could look at it as an examination of failed leadership. Or perhaps as a criticism of corporate motives, or mixed up priorities. There’s a cool structural engineering slant throughout the book, and also some rumination on the potentially flawed structures of decision-making hierarchies. There’s a really interesting thread about the idea of community versus personal responsibility. On El Faro it seemed so central to keep the ship watertight – maybe the most important thing on a boat -- that it had become everyone’s job, but was really nobody’s responsibility. How relevant at Tabor, where we take group responsibility for the asset – our community – we most care about.

There are these many views and points of interest, and as is typical we all likely settled generally into a few that most resonated with us. As the Captain of the Good Ship Tabor, for example, I found it easiest, and saddest, to see the events through the eyes of the Captain. It wasn’t that I didn’t look through the eyes of the others. I did, and this is what made the book so excellent to me, the chance to see a shared experience and outcome through many different perspectives. Of course we were looking through a fair-weather lens at a hindsight event. From our perspective and knowing the outcome we found it easy to feel we had a good sense of what happened.

Ms. Slade did exhaustive research to discover the details, and I can’t wait to hear more from her. But despite her good work and our sense of confidence, seeing it after the fact, we really have little way to know the actual, real-time perspectives of those described in the book. Nobody set out to, or wanted the ship to go down, or for lives to be lost, especially their own. Yet somehow, given all the same general information or at least the opportunity to access it, what we perceive today as easily understandable and clear, eluded those on board. Somehow, they didn’t see the totality of what was really happening. The danger was not in the weather. It was not in the engineering modifications to the vessel. It was not in untimely communication, or perhaps even in poor communication or decision-making. A boat can hold only one course at a time, and it turns out most people can only hold one perspective at a time. The trouble with you is the trouble with me, and it was the trouble aboard the El Faro, too. Lots of good eyes, but lots of difficulty seeing. People involved seem not to have understood the entire consequence of the unasked question – who’s perceiving this rightly? Out of habit, stubbornness, or blind – yes blind -- confidence in believing “boats like that don’t sink,” important perspectives were left out of the truth of the threat. They were never used as the tools – the life-saving tools – they might have been.

There is no criticism in this. What happened there happens to all of us. The consequences may be less for us than for the El Faro crew. But here aboard this good ship they are no less important for the ways in which we go about our living and learning. If our voyage of discovery is tied up in becoming knowledgeable, thoughtful citizens, and relevant to a world that is desperately waiting for you to join in – overcoming this trouble, seeing it for what it is seems essential to our purpose.

We’re all subject to a sort of perspective, visual myopia, the difficulty of a narrow view of whatever we’re looking at. It is physical – there are limitations to our fields of sight. It is cognitive – there are limitations to the number of things we can attend to and a nagging tendency for our brains to routinely and unconsciously filter information. It is metaphoric – we confidently conflate seeing and knowing, without fully accounting for the limitations of the comparison. This is the trouble I refer to in my little jingle, and the trouble comes from a pretty simple recognition. Both in physical sight and mental perspective, we don’t see well or broadly. Yet most of us generally equate seeing – physically or mentally -- with knowing. And once we know something, we are not easily moved from that position. We use our perspective to build what we think of as our true view of the world around us. Within this true view are our values, our opinions and our beliefs. You have all heard the phrase perception is reality. Your perception, derived from what you can see of the world -- this is your reality. You think of it as at least trustworthy, if not outright true, because – well – that’s how you see it. From the perspective you have. But what if our confident and accurate-to-us perspectives are put into conflict with someone else’s? The fallibility of our sight, and therefore the fallibility of our understanding, becomes very real and very consequential.

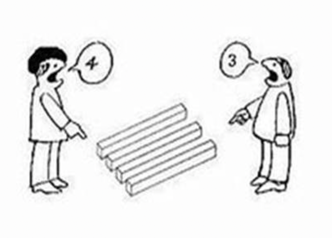

Let’s consider the homework example I sent you last night – the cartoon of two people looking at what we, as third party viewers, can see is an optical illusion. To one person, there are 3 bars, to another 4. We can observe that neither is seeing it wholly accurately, and we also can see why they believe what they see is the truth. There are many good eyes here, but trouble sure enough, especially if someone asks the question: Who is correct? To either of the people, from where they are seeing it, the answer seems so simple. Why anyone can see there are 3. Well, of course there are 4. Both are correct, if they add the phrase “from here,” but they probably won’t because they “know” the answer. In a benign example such as this, each might depart feeling good about their correct answer, and wondering what was wrong with the other person. But what if they needed to solve the disagreement for some reason? What if being incorrect had serious consequences? So, this storm we’re coming into on the El Faro: Is it a ship-threatening hurricane, or like day to day weather in Alaska? Are we in danger of real harm or a really rough ride? Is there a worrisome amount of water in the hold, or just a nuisance level?

In the cartoon, everybody and nobody is correct – it’s an illusion. It would be tempting for us to say that the world does not work that way, that real life examples are not cartoons, and that this sort of illusion is not a true reflection of the viewable world of experienced reality. We’d be wrong, though. For, despite some objective reality out there, the cartoon reminds that we can only see the part of a problem we see, from the very particular viewing angle we have; and if we only see part of the picture, we are likely only to understand part of the picture. Consider that the very same person from three different perspectives would give all three answers confidently. There are 3, he might say from here. There are 4, from here. It’s neither, it’s an optical illusion from up here. The person didn’t change. The object didn’t change. But the answers did, as quickly as did the perspectives, and so the truths were in conflict. Weird isn’t it?

This is where that perspective myopia comes back into play, and the second part of your cartoon homework becomes relevant. What is less viewable to us in such examples is the cognitive filtering I mentioned earlier. For physical sight as for mental perspective, the arc of our field of attention is relatively small. We are gathering information constantly, but our brains are left to process and to prioritize it. Some of this it does in very helpful ways. If you are looking directly at something, you can see all the details. Move to the periphery of your vision, though, and there is less detail, but more sensitivity to light or movement. Your physical eyes and your interpretive brain together have prioritized. “Tend to the details of this focus here, but don’t get surprised by something just outside your focus here on either side.” For an auditory example – think how easily our brain filters out all the details of the noise in a crowded room, but filters in even the mere mention of your name?

Our brain, in truth, does more than prioritize. It actually impedes or suppresses information it believes to be less relevant. We can look another direction to expand our view or get more details, or concentrate our attention on one single conversation in the crowded room to hear the gossip. But we have to decide to do so. The default of our brain is to keep those other information streams out. It’s almost Darwinian, as if some of the information is being driven to extinction by other bits. This is why, in the second piece of homework I sent you last night, you can see either the faces or the vase, but never both at the same time. Because you know they are both there, your brain will allow you to toggle back and forth – but it will never permit you to hold both perspectives at the same time. It functions to help you see and tend to a limited piece of reality at any given moment. That’s the default mode.

This cognitive default mode is really the trouble. It’s not our good eyes, but rather our one really efficient brain. It is hard to overcome. We see a lot. We are perceiving machines, and we take in tons of information visually and through all our senses. We are not, however, big, broad, alternative thinking machines. It’s not that we can’t be, or are not ever. In moments of creativity, when we allow ourselves to reconcile perspective conflicts, we are conquering our naturally limiting brains. It’s such an accomplishment. We feel pleasure in this -- the fun of play, the glory of curiosity, the exhilaration of trying new things. But this is not our habitual state (at least as adults), especially when we are comfortable in our view. Put to a test, in fact, we might entrench in our perspective, allow our brains to limit the view to just the faces, or just the vase. At such times we see our own perspective as clear, our truth as unwavering. At such times, we struggle to move from our assertions of confident rightness – “It’s 3 darn it!” – to an open question of curious uncertainty -- “I wonder why she thinks it’s 4?” This second question is so difficult, because it involves the empathy of stepping out of your truth and into someone else’s. How unsettling? But this phenomenon, this discomfort, is not a character flaw! It’s your brain, and you could simply decide to see the question differently and learn the skills of doing so!

The big problems the world faces today are illusions of a sort. They have multiple answers, and many different ways to be seen. As a third party observer of the cartoon our lives sometimes feel like, replace the numbers, 3 or 4, with personal values or perspectives – things like freedom on one side and the sanctity of life on the other, as in the debates about gun violence or abortion; the order of law on the one side and the messiness of compassion on the other, as in the immigration debate. The promise of livelihoods on one side, the promise of a healthier future environment on the other, as in the climate debate. Turn your illusory vase and faces into matters of real consequence, and try to pull one non-conflicting, but still true, image from the illusion. Your brain may make it hard, your perspective may make it seem impossible. But your heart – the caring half of your committed citizenship -- knows that there is more than one answer, because it knows there is more than one perspective. Do the people who desire freedom from the threat of mass shootings, really not believe in the constitution? Are the people who want freedom to own guns hoping others will be randomly killed? It’s 3. No 4. It’s a vase, it’s two faces. It’s a duck, it’s a rabbit. Exactly. The trouble with you is the trouble with me.

On our school t-shirts – are they purple or blue, by the way, from your perspective – I’ve proposed a central aim for the year to be more skilled seeing, seeing from perspectives other than our own. THE VOYAGE OF DISCOVERY CONSISTS NOT IN SEEKING NEW LANDS, the shirt says, BUT IN SEEING WITH NEW EYES. I do not mean to suggest that there are not new discoveries out there. Of course there are, and how incredible to find them. I’m asking, though, that we take the landscapes that are already familiar to us – the confident and solid geographies of our values and beliefs – and actively decide to see them differently and from other angles. The way we are constituted makes this hard – our efficient brains, our two good eyes. We’ll have to work at it. The many influencers in our lives – our leaders, sometimes our friends, media outlets – add to the trouble. Inclinations within us and forces without convince us that there is only one way, that the answer is binary, that the truth as you see it is the truth. But find someone who is absolutely certain they know the answer to a problem – even a simple problem, 3 or 4 – and I’ll show you someone who has eliminated all the other perspectives. How limiting, how static, how unseeing. Really, how unthinking.

The trouble with you is the trouble with me. We’ve got two good eyes and have to work really hard to see. But here at Tabor we could decide to see more skillfully, and to know and understand each other more deeply as a result. We could practice seeing from the viewpoints of others, so that our own perspectives are broadened and made richer for the testing of them. We could make as our community default a mode not of impedance, but of empathy and curiosity – asking the question, “I wonder why it looks that way to him or to her?” We could do these things and others, committing to Tabor as a place of ideas and perspectives -- not the defense of ours or the suppression of others’, but the use of them as the learning tools they are. We share in the trouble, the problem of not seeing well. Let’s share in the decision to do it better, seeing through new eyes, new ways of thinking and new ways of understanding. There’s no trouble in that, no trouble at all as I see it, in the great learning community we share.

Thanks for listening.