The "Superman" pose, the picture that everyone who flys on the KC-135 takes

Alex Pline ’80 is a Project Manager at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Headquarters. After more than three decades at NASA, Alex is now planning for retirement. Bonnie Punsky ’04 reached out to Alex to learn more about the future of America’s space program, how soon humans will be walking on Mars and the Moon, and what it’s like to ride the “Vomit Comet.” In his retirement, Alex will focus on a new “career” in bicycle advocacy and urban planning, as well as doing some long distance off-road bike touring (“bikepacking”) and traveling to sail as many Snipe regattas as possible with his wife Lisa.

Q. How long have you worked at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)? Can you tell us about your role there?

A. I have worked at NASA for 34 years, essentially my entire working life since graduate school. Of course, this kind of long term relationship is quite rare these days, but not surprising for NASA as our people tend to be extremely passionate about the work we do. However, despite this long tenure, my experience has been multifaceted. My degrees (BS/MS) are in Mechanical Engineering with a specialization in Fluid and Thermal Sciences and I worked on a NASA project as a graduate student. After school I started at the NASA Glenn (né Lewis) Research Center in Cleveland continuing the work I did as a student on a low gravity fluid physics experiment that eventually flew on two Space Shuttle missions in 1992 and 1995. It was a very exciting time in the low gravity research community as the activity in the field was very robust and experiments were starting to fly regularly. Leading up to the mission, I had some extremely memorable experiences in the lab, flying on the “Vomit Comet”, a NASA aircraft that experienced 30 second periods of “zero-g” by flying parabolic trajectories (fun fact, I have 5 hrs of “zero-g” time all in 30 second chunks), and meeting and training astronauts on the experiment operation. I was able to view both launches close up at the Kennedy Space Center and spend the two week missions “on console” monitoring the experiment operations and analyzing data as it was sent to the ground.

When I moved to NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC in the late 90s, I made a career pivot to information technology as the World Wide Web really gained a foothold at NASA. The promise of the web captivated me with so much potential to tell NASA’s stories. In the twenty years since, I have been part of a larger and now well organized group of IT professionals and creative content developers that has produced some of the best content on the internet and pushed it to millions of people using the main nasa.gov website. I’ve also had the honor of working with a lot of talented and dedicated engineers developing internal web-based software applications that help them get their jobs done more efficiently by reducing tedious and manual aspects of their work.

Q: NASA is planning the first launch of astronauts from US soil since the 2011 retirement of the Space Shuttle. What motivated the return of manned space launches? What are the biggest benefits and challenges of partnering with SpaceX?

A: Escaping the clutches of Earth’s gravity is the first challenge in any kind of space exploration, human or otherwise, as it requires tremendous amounts of energy. The promise of the Shuttle was to provide frequent, low cost access to orbit through a reusable vehicle, but after 30 years of experience and the loss of two vehicles and crew, it never met the promise. From its inception, NASA has always used private contractors to design and build spacecraft. However, as the Shuttle program was being phased out a new paradigm was implemented for contracting with private companies to build and operate launch vehicles. Instead of the government providing a set of performance, construction and management requirements (i.e. we tell them what to do, how to do it and we were the only customer), the Commercial Resupply and Commercial Crew programs requested that private companies provide “services” that NASA guarantees to purchase (.ie. we told them what we want to buy, the performance requirements, but did not tell them how to do it or restrict to whom they could sell the same service). These programs were implemented as “competitions” where NASA would fund - along with significant private funding from the competitors - various phases of the development. At each large milestone there was a narrowing of the competitors based on whether they met the published objectives. Ultimately, the competitors were able to innovate because they were free to explore any methodologies or technologies they believed would provide the best solution.

Q: Can you tell us about the Mars Rover scheduled to launch later this summer?

A: The Mars 2020 mission scheduled for launch this summer and landing early in 2021, has the next iteration of robotic rover (named Perseverance by a Virginia high school student in a contest - how cool is that?). This rover is as large as a small car, about 10’ long and 9’ wide and, as was its predecessor Curiosity (golf cart sized), powered by nuclear material rather than solar cells. Power is generated by the decay of a baseball-sized chunk of plutonium which generates heat that is converted to electricity with no moving parts. Not as powerful as what we would consider a “nuclear reactor” used in terrestrial power generation, but very reliable and very safe and will provide enough power to maintain the rover well past the intended mission length of two years. The capabilities of Perseverance will allow it to roam autonomously over a wide range, better understand the geology of Mars, and will collect and store a set of rock and soil samples that could be returned to Earth in the future. In addition to the scientific measurement equipment, there are two technology demonstrations on the mission: The “Mars Helicopter” and a system that will produce oxygen from Martian atmospheric carbon dioxide. In the future, an operational helicopter - a challenging problem in the 100-times thinner Martian atmosphere - would provide significant mobility on the Martian surface for scientific data collection, and extracting oxygen from the Martian atmosphere could be used for propulsion back to Earth during an eventual human missions, greatly reducing the amount of material humans need to bring with them. This is really the only practical way a human Mars mission would work. I’m really excited to watch this mission and see the new understanding of the planet that results from the scientific instruments.

Q: NASA hasn’t sent astronauts to the moon in almost five decades. What brought about the goal to return to the moon by 2024? What are the biggest challenges to this goal?

A: In my 30+ years at NASA, there have been several “Back to the Moon and to Mars” initiatives. In 1989, President George H.W. Bush announced the “Space Exploration Initiative” calling for constructing the Space Station, sending humans back to the Moon "to stay," and, ultimately, sending astronauts to explore Mars. In 2004, President George W. Bush announced “The Vision for Space Exploration” which sought to implement a sustained and affordable human and robotic program to explore the Solar System and beyond. It also called for a human return to the Moon by the year 2020 in preparation for human exploration of Mars and other destinations. Both initiatives were as ambitious as the Apollo program, but with nowhere near as much funding or political support they were ultimately scaled way down to fit the realities of the available budget. While President Trump’s initiative is the latest incarnation of this type, the circumstances are different thanks to work done in the interim. The International Space Station is essentially complete, the commercial resupply and cargo programs have come to fruition, and the development of NASA’s own long range crew capsule Orion and launcher the Space Launch System are close to completion. Along with international participation, the goal of getting back to the Moon is now within our grasp via the Artemis program. While doing it within the allotted time frame is a political decision, NASA is working hard to reach this difficult, but achievable goal in an apolitical way. Difficult challenges always require some compromise, but people at NASA and NASA’s contractors work diligently to insure the US gets the best result from the investment. The challenge will be to implement the pieces of the Artemis program in a sustainable and incremental way so each step can build on the prior to keep the program moving forward. It is my hope Artemis will continue regardless of political change and perhaps even land a human on Mars in my lifetime.

Q: Are there skills you learned or experiences you had at Tabor that helped prepare you for your career at NASA?

A: Certainly the academic rigor, especially in math, physics, and chemistry was a real benefit for me. I was a rather unfocused student prior to coming to Tabor and the structure and mentoring by specific faculty really helped me. I especially liked Paul White as a math teacher and I came to know Gunter Suckert well through classes and while working under him during the summers in the Maintenance Department; their work ethic made a big impression on me. When I got to college (Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland) I was well prepared to thrive. There are certain “larger than life” individuals whose large gravitational pull have a substantial effect on your life trajectory. These were two for me at Tabor and those experiences taught me to keep an eye out for other role models that would provide a gravity assist flyby. Joe Prahl, a professor at Case, was another whose gravity assist put me into the NASA orbit. Sorry I can’t resist these space metaphors!

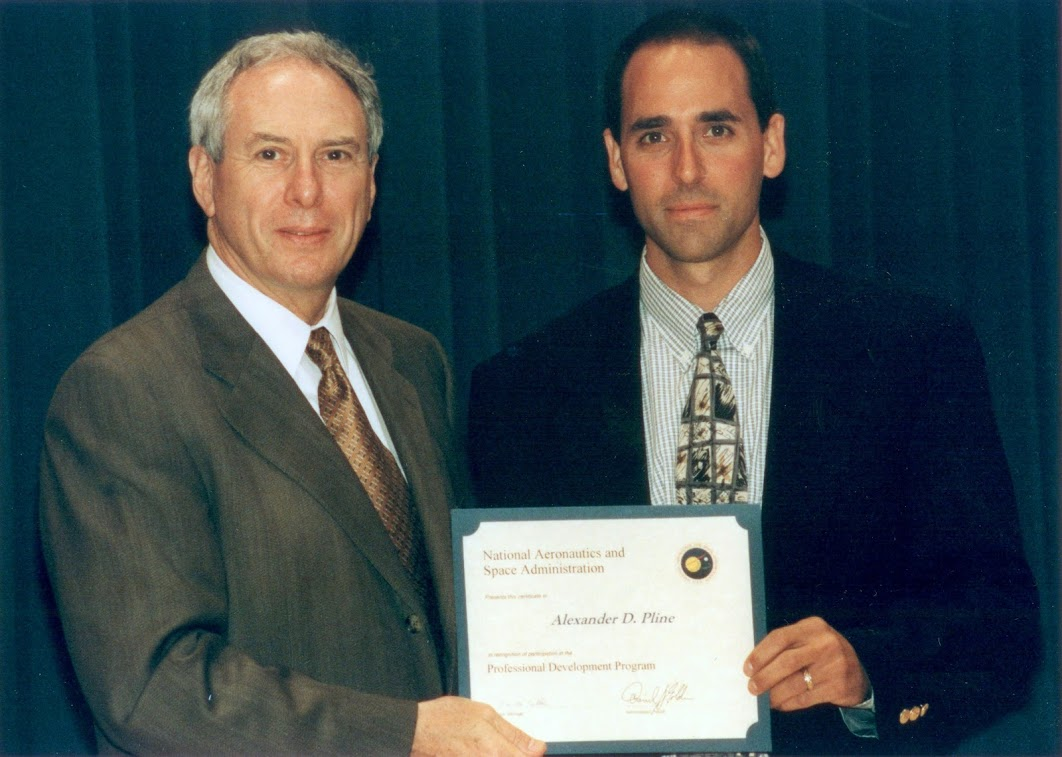

Alex (right) with former NASA Administrator Dan Goldin (left), the longest serving NASA Administrator, after participating in NASA’s Professional Development Program at NASA Headquarters in 1996. According to Alex, the best remembered "Goldinism" was "Better, Faster, Cheaper" to which most people appended "pick two.”